Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears

0

0

0

0

- Meaning

- The phrase "Friends, Romans, countrymen, lend me your ears" is a masterful example of persuasive rhetoric. Antony is commanding attention from the crowd in order to sway their sentiments, following the assassination of Caesar. It’s a prime example of how to engage an audience, asking for their attention (lending their ears) to listen to what he has to say. It illustrates the use of ethos, gaining the trust of the audience by invoking shared identities (friends, Romans, and countrymen).

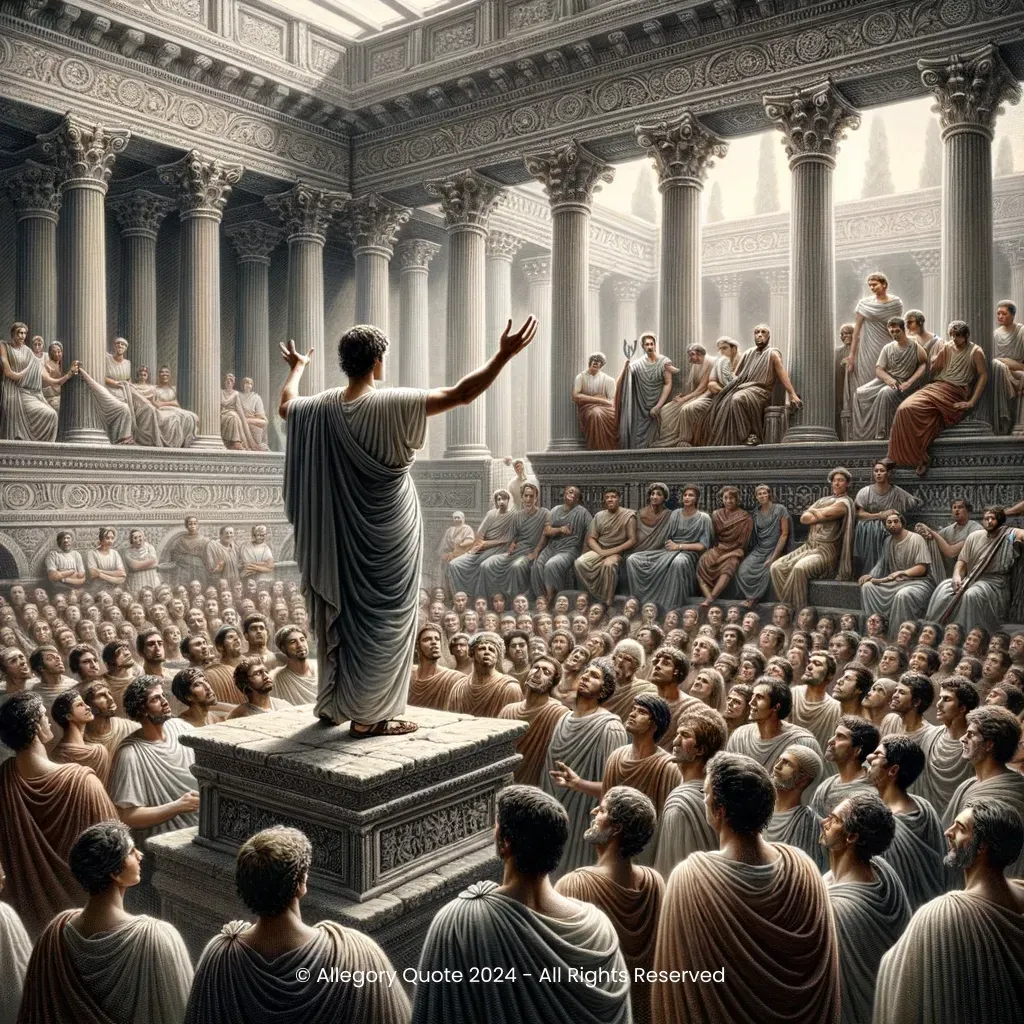

- Allegory

- In this image, Mark Antony stands as the central figure, emphasizing his role as the speaker. The raised platform symbolizes his authority and the importance of his speech. The diverse crowd embodies the Roman populace, highlighting the widespread importance of his address. The Roman architecture sets a historical context, reinforcing the setting of ancient Rome. The varying expressions in the crowd convey the emotional impact of Antony's words, illustrating the power of rhetoric and persuasion. Altogether, the image captures the tension and significance of the moment, inviting viewers to reflect on the enduring influence of powerful speech.

- Applicability

- This phrase highlights the importance of gaining the audience’s attention and trust before delivering a critical message. In personal and professional settings, capturing your audience’s attention and establishing a connection through shared identities or common ground is crucial to effective communication. Whether delivering a presentation, giving a speech, or even engaging in a casual conversation, starting with an appeal to your listeners can make your message more impactful.

- Impact

- This phrase has had a lasting impact on literature and culture, often quoted to emphasize the need for attention or to introduce a pivotal speech. Through this line, Shakespeare exemplified effective rhetorical strategies that have influenced public speaking, political rhetoric, and literature for centuries. In cultural contexts, it's frequently alluded to in discussions about influential speeches and persuasion techniques, highlighting its continued relevance.

- Historical Context

- "Julius Caesar" was written in 1599 or 1600, during the Elizabethan era. The historical context is significant as it was a time of political intrigue and exploration of themes of power and betrayal, reflective of the play's content. The Elizabethan audience, aware of the political machinations of their own time, would have found the themes of power struggles and public manipulation particularly resonant.

- Criticisms

- There aren't major criticisms or controversies specifically tied to this phrase itself, but Shakespeare's works, including "Julius Caesar," have their share of interpretations and debates, particularly about historical accuracy and the dramatization of real events. Some might argue that using historical figures and events for dramatic purposes can distort public perception of those events.

- Variations

- There are no significant variations of this exact phrase, but its rhetorical structure has been widely imitated. In different cultural contexts, the appeal to the audience's attention and shared identity remains a universally powerful technique.

-

The golden age is before us, not behind us.

-

Cowards die many times before their deaths; the valiant never taste of death but once.

-

I'm gonna make him an offer he can't refuse.

-

Qui nescit tacere, nescit loqui.

-

O brave new world, that has such people in't!

-

Out, out brief candle!

-

Brevity is the soul of wit.

-

Beware the Ides of March.

-

But, for my own part, it was Greek to me.

-

The course of true love never did run smooth.

-

My tongue will tell the anger of my heart, or else my heart concealing it will break.

-

Parting is such sweet sorrow.

No Comments